Just over ten years ago, in May of 2008, AMC aired what is arguably the greatest scene in at least the first season, if not the entire series of Mad Men. In it, Jon Hamm as Don Draper, stepping from engaging character to television legend, pitches a group of bored Kodak executives on his campaign for their new slide projector with a “wheel” mechanism that organizes and displays the slides. The pitch is pure genius: artistic, insightful, and emotional. 10 years later, I still identify with Harry Crane as he jumps up and runs out of the room in tears:

The power of the scene comes from how deeply the voice over expresses the most human of emotions, nostalgia, while the simple visuals of candid family moments evoke in us the same longing that is being described. Citing “Teddy the Greek,” Draper translates nostalgia as “the pain from an old wound,” though the definition seems to disregard the presence of the Greek root “nostos,” which denotes “return,” and is linked to a genre of poetry that circulated in Greece which focused on heroes returning home from the Trojan War and the various tribulations they encountered in doing so. While Homer’s Odyssey is the most famous example of this, its opening books (often called the Telemachiad) feature a survey of varied returns that Odysseus’s son Telemachus sees the aftermath of as he travels throughout Greek states trying to learn what became of his father. This section of the poem is important to the account that follows, but scholars also believe it to be a kind of anthology of poems, many now lost, that were already circulating about these other figures.

Return is, of course, central to what Draper says above, noting that in returning to these moments in history we revel in the pain of that old wound, of the loss it embodies, and in the change an old image makes visible. This is perhaps the most ancient and eternal of human emotions, as it make visible our mortality, but it offers joy as well, in the memory of happiness and the knowledge of growth and development. The pitch closes with Draper evoking this joy, embodied in the name, when noting how the carousel “lets us travel the way a child travels, around and around, and back home again, to a place where we know we are loved.”

The scene, like so much of Mad Men, is genius because of the layering of text, subtext, and metatext that unfortunately, is often lost on a wide slice of the audience. Too frequently, Mad Men is remembered for its unparalleled coolness. The art direction, costuming, and props offer a visual feast that attracted viewers from the opening strings through to the always baffling “next time on AMC’s Mad Men…” But beneath the patina of cool is the reality of a privileged overclass amid a wash of 60’s change and revolution. Too often viewers looked at the show’s top layer of cool with that same nostalgia, and ignored the fact that it was authorized by privilege. In that beautiful scene above, we remember Don’s words, not when he calls the only female character present “Sweetheart.” Whether we lived in the period or not, we fantasize of being the type of man Draper was, not concerning ourselves with how characters like closeted Sal (present in the room) would remember this period of his life.

Most of all, while viewers are moved by the emotion of the scene, and the contrast it draws between Draper’s professional and personal lives, too many seem to miss Weiner’s key metatextual point: the gross commercialization of humanity. Were this a man philosophizing, maybe this voice over would represent that triumph of human goodness over the sins of greed, pride and lust (it is Don Draper, after all), but this is a pitch meeting and whatever art the genius Draper has created is only as good as the bounty it will bring in. This is, of course, the point underscored by Mad Men’s uneven final season, which finds Draper seeking fulfillment outside of Manhattan. In the much-memed final image, Draper, meditating in a beautiful cliffside yoga retreat doesn’t find himself or a greater truth worth knowing, he finds the greatest television advertisement of all time.

The Draper Legacy

Revisiting this scene in light of the intervening years demonstrates what Don Draper and Matthew Weiner seem to have always known: few emotions can rival the absolute power of nostalgia. Over the course of the last ten years, nostalgia has grown from a pleasant and reassuring influence on American life into perhaps its dominant mode, infecting culture, society, and politics in ways that, while unexpectedly damaging, are perhaps the most natural outcome of the profitability of nostalgia. Once Draper’s real life marketing counterparts unleashed the emotion on America, it took root and blossomed in ways that dictate life’s dynamics from early adulthood onward. This concentration on looking backward has caused widespread stagnation in creativity and culture that seems to relegate us to the same endless cycle of the carousel, traveling around and around but never achieving forward motion of any sort.

I express this indictment fully cognizant of how willfully I give myself over to this emotion. As a child of the 80’s, it is my generation (and very often me specifically) that continues to fill multiplexes for lesser sequels of classic films, and that jumps at the chance to stream a sitcom revival that we will ultimately be able to say disappointed us. Beyond this, the power of nostalgia has granted dark powers to social groups that seem to always dictate what film, television, and video game companies create: white, male, upper middle class cisgender heterosexuals. While not inherently more problematic than the original privilege, this added level of nostalgia has metastasized in the internet age to create a generation that either gets what they want, or will burn down the world in response. Look no further than the current crisis engulfing Star Wars fandom, or the lingering effects of gamergate on the video game industry.

Since the 2016 election, the United States has finally become aware of just how far amok this segment of the population has run. In the revealing of Alt Right internet groups and the violent hate march in Charlottesville, to make no mention of the innumerable mass shootings and racially-motivated terrorist acts committed by young white men, larger segments of society seem to finally see the ways in which this group, left unchecked for so long, needs to be reexamined and reformed if we are to find relative balance in the modern age. Into this conversation, I want to assert the centrality of nostalgia and the way the over-commercialization of that emotion has led to a generation that, while easily laughed off as narcissistic, actually suffers from an acute lack of formative identity, the hollowness behind the ache of nostalgia.

Arrested Development

In the 2000 film classic High Fidelity, Gen X megastar John Cusack gives a performance that is the epitome of detached cool, and amid the many highly quotable nuggets of wisdom, he gives the burgeoning millennials who filled the audience a mantra to live by: “What really matters is what you like, not what you are like.” This encapsulation of the record store ethos of the larger film echoes as instantly true to almost everyone: when we leave the safe confines of our family and seek out our new tribe, those initial connections are most frequently found in concert halls, comics book stores, or the sticky-floored multiplex. As the character notes, “Call me shallow, it’s the fucking truth.” Like children comparing lunchboxes, we learn about who surrounds us based on the art and story that motivates and excites them. In these shared passions we find kindred spirits, and build from this foundation into more authentic and genuine forms of kinship, friendship, and love.

But what if that evolution never comes? In the fabled small town of old, the high school might organize itself by “what you like” cliques: the jocks, the nerds, and the fearless theatre geeks, but these affiliations wouldn’t be seen in the town pub. As individuals mature and change, the childhood attachments would fade as well, returning each from Neverland to the land of grown-ups. Yet, as many sociologists (and crabby baby boomers) have noted, the period of adolescence has been continually expanding beyond young adulthood and across the early and mid- twenties. Where once high school graduates were pushed to abandon childish things and embrace the wider world, now the coolest kid in the dorm may be the one with the cartoon sheets or the throwback movie poster.

Sociologists studying the issue have found myriad phenomena effectively shaping this prolonged adolescence, and oft-noted among them is the profitability of nostalgia. For many upper middle class individuals, early adulthood is the period where (even with student loan debt) you are able to experience greater autonomy in purchasing power, as well as greater control over personal space. Striking at this moment, marketers have found lucrative ways to create clothing, high-end collectibles, and housewares that revel in the nostalgia of childhood properties. Look no further than the Pottery Barn Star Wars collection, or the sudden prevalence of merchandise themed around the Disney Afternoon block of programming that many children were raised on throughout the 90’s.

Perhaps most symbolic of the trend is the line of Funko Re-Action figures which reanimate dead commercial properties from film and television and offer children from that era to finally have their 3 ¾ scale Marty McFly, Ridley, or Elliot. The marketing of these products instills the message that the consumers were owed these products. They are the missing piece of childhood that they always wanted (but never needed) and it is about time that they received what is due to them.

Any trip to the local comic book store, book store, or mall suggests a huge market for products such as these, and these products in turn demonstrate the market demand for the property to be reignited, leading to new Tron movies, Blade Runner sequels, Dark Crystal comic books, and new episodes of Ducktales.

How then can we not expect young adults to bask in this nostalgia and find themselves fulfilled in the recurring loop that creates the ache, offers the salve, and sells the t-shirt. Even when young adults move on to marriage and child-rearing, the push is there, perhaps even stronger, to buy children the perfect retro toy, or share with them your passion for the intellectual property you enjoyed as a child.

Like If You Remember…

While rampant consumerist nostalgia creates the unending opportunity to celebrate memories with paychecks, social media harnesses the same set of emotions to monetize connections and further erode the line between what you like and what you are like. In the cultivated gardens of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, like-minded users find connections and community among those who, by virtue of age or disposition, share the same passions. This not only allows for prolonged adolescence, but rewards it continually, by offering the stimulation of likes and retweets.

The epitome of this trend has to be the ubiquitous meme, propagated by all sorts of local radio stations, that uses an image of an old artist, film, or piece of technology and instruct users to like or share the image so that everyone can know that they remember this thing:

Perhaps because memes such as this peddle in pure gratuitous nostalgia, the popularity of such images is in no way limited to any single demographic or age group. Due to this, it’s hard to argue that there is anything innately harmful about such memes, as they really are just a celebration of membership within a particular community, and their abundance suggests that almost all communities, regardless of privileged status, can find common cause and celebration, even identity in the shared memory. However, it doesn’t take much searching to find the ways in which subtle sociopolitical messages creep into memes to move from a simple celebration into a statement of superiority, or into derision toward another group.

The half step measure shown here takes the image of a classic Tom and Jerry cartoon and turns it from a simple shared memory into a an assertion of the superiority of one group (in this case, I would say age group) over the others. Encoded here is the further political message that children should not be sheltered from the famously violent cartoon, as the children who grew up on it were, clearly, “awesome” and certainly not negatively affected by the violence they were exposed to. As if age superiority weren’t enough, it’s also important to note that another reason Tom and Jerry isn’t regularly shown on television today is its needless promulgation of harmful stereotypes of Black women in the character Mammy Two Shoes, who appears as a blackface caricature of midcentury domestic servants. To share the above image as a sign of one’s “awesome” childhood is to erase these problematic dynamics, and the violence they inflict in favor of reveling in the simplistic childish joy you once knew. In this way, nostalgia has been weaponized into Anti-PC culture attitudes, perhaps without the sharer even being aware of the impact the image has on those not from the privileged group.

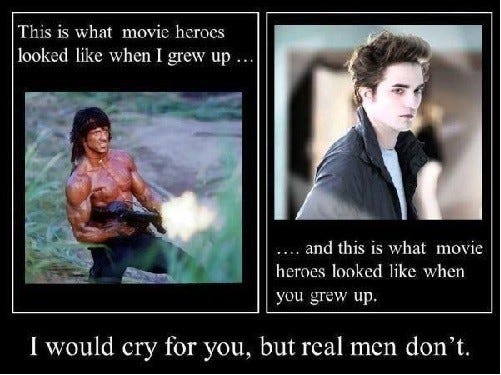

The extension of this same trend, memes like this final example offer a full-throated endorsement of a regressive social value as an expression of that same nostalgia. Fully weaponized here, the meme goes from subtle expression of superiority into an outright indictment of one group by another. Here, an outmoded form of masculinity is asserted to indict healthy emotional expression. As with all stereotypes, the picture presented is woefully incomplete, using a single piece of art from each era to represent the full array of male identity. Whether or not the viewer identifies with Rambo, Edward, or neither, there is a clear message about where the sharer feels you should identify.

These memes, and the countless hordes they represent, represent a new and significant means of identity expression in the internet age. The specific trajectory I have shown briefly in these three is meant to demonstrate the slippery slope from one category to the next and how the innocent celebration of membership in a community (age, race, gender) is easily co-opted into an attack on others. Such weaponized nostalgia doesn’t sell slide carousels, but instead works to continually divide and fragment us into ever-smaller communities.

Make America Great Again

Inevitably, like far too much of American society today, this trend and blog entry have led us inevitably to the rise of Donald Trump and the ways in which he harnessed the power of nostalgia to fuel his campaign and the rise of regressive social views in American politics. Look no further than #MAGA to see the power of nostalgia and the ways in which conservative values have been reshaped by 46% of the electorate into a rallying cry to repeal progressive policies around minority and women’s rights advancements. Trump voters from their early 20’s into old age vary widely, but all endorse the view that life was somehow better before (in an unspecified time) and that the path forward needs to be to recapture the social attitudes of the past in order to somehow bring prosperity to the present.

This link between online nostalgia memes and the branding of the Trump campaign, to be clear, is absolutely deliberate and constructed. As has been well documented, Steve Bannon purposefully courted the online followers of Milo Yiannopoulis, a community that had grown out of anger at the intricacies of World of Warcraft gaming, and used their not inconsiderable skills at online organization and meme rhetoric to create a passionate internet presence churning out content which, with the help of a not insignificant number of Russian bots, made Twitter a revelry of conservative nostalgia. With Trump as their mouthpiece, the groups rallied around anti-PC culture ideology, rising to action around a media that finds easy content in calling out racist, sexist, and otherwise bigoted behavior. To state it more simply: when you readily accept that real men don’t cry, it’s much easier to accept that real men grab pussies.

In other words, the Trump campaign and the social dynamics it rode into office built off the long-seeded ache of nostalgia that marketers and companies had trained the American public to crave. In light of rapid social and demographic changes facing a country where the majority of babies under age four are no longer of the dominant racial class, and where rapidly changing views on gender and sexual identity create anxiety in even well-meaning but unsure individuals, the siren’s call of nostalgia presents the path of least resistance. Though few would admit it, it is the allure of privilege, calling back to a time where just being white or cisgendered or heterosexual guaranteed comfort and a lack of challenge. Those seeking that comfort were drawn to a man who, as privilege incarnate, offered to make their lives easier. While many would claim their enlistment in that movement as wholly unbiased, in reality it placed the suffering of others beneath their own comfort at every level. Nostalgia moved from celebration to subjugation, and whether or not supporters recognized it, their actions were shaped by bigotry.

To assert this is in no way revolutionary, and I assume that I am largely preaching to the choir of my own bubble. But acknowledging this relationship has helped me recognize the humanity in my family and friends who are a part of this moment, and to see how their minimally callous self-celebration became, through revolutions of the carousel, aggressive indifference to people unlike themselves.

“I’m Mary Poppins, Y’all!”

If we are ever going to disentangle nostalgic cravings from the bigoted forces that have claimed them, it is going to rely on us, the consumers of pop culture, being able to reckon with the reality of nostalgia as a pleasing emotion, but a hollow experience. To re-encounter the same characters, art, or themes throughout our lives is the junk food of culture, and while tasty, it will not provide the nourishment needed to challenge us toward real progress. We need to find ways to break free of the carousel and find art and culture to challenge us and push us toward new ideas, not just wallow in the familiar.

In a classic and memorable Daily Show segment from 2010, a rather floppy-haired Cassandra (John Oliver) explored this exact problem, and explained to us the reason for the nostalgic ache: http://www.cc.com/video-clips/e08ybj/the-daily-show-with-jon-stewart-even-better-than-the-real-thing.

As noted, the real message is that your memories of life as a child are colored by the rosy tint of childhood innocence. We will always believe those to have been better times, as it was a time before we had to grapple with the reality of understanding who we were and how are actions and ideas are impacted and impact others through systematic oppression and institutionalized privilege.

But, as the box office and the streaming services demonstrate, nostalgia as cultural dynamic is still highly profitable and will thus continue as a guiding force for some time to come. While one solution would be to simply reject all products of nostalgia, this seems unrealistic and perhaps even unnecessary, if you can consume nostalgia in proportion with other culture. That is, revel in the reminder of great things past, but find challenge in new experiences or art, even if that, from time to time, leads to dissatisfaction. We may crave franchise reboots and rehashes from a sense of safety, but we sacrifice new ideas and values in result.

In fact, the lesson we need is in the Odyssey. The opening sections of the book demonstrate the power of old stories and of the ways in which they should be engage. The genius of Homer’s opening is in the fact that the hero of the poem, Odysseus, is nowhere to be found in the first books. As we relive the nostos events of the varied heroes of antiquity, we do so through the eyes of not the generation that experienced them, but of the next, understanding the events related in order to inform the future. Telemachus sees what kind of leader these men were and what they needed in order to better understand what he will need to do in the future. The audience of the poem sees the pitfalls of lesser heroes so that they might understand the heroism that Odysseus will show. Only in this way can nostalgia move away from self-referential navel gazing and forward to what more can be achieved using the knowledge of the past.

This lesson is in modern art as well: Harry journeys in the pensieve (literal memory) of one generation so that he is ready to lead his own. Rey rescues the sacred Jedi texts from Ach-to to shape her own path forward. This is the lesson our culture needs to take and only then will we spend more time envisioning what could be instead of mourning what once was, breaking the carousel and freeing ourselves from Draper’s sales pitch. Such work requires the rejection of simple comfort and the embrace of discomfort, which is the place where real growth and development happens.